Returned to northern Appalachia to attend the funeral for our beloved cousin. A second cousin, I think is the proper term. The eldest daughter of my mother’s sister’s daughter. She passed away at 49 from an undiagnosed cancer that was found while she was in for a routine surgery a week earlier. She was the second of my second cousins to pass away. Both women and both from cancer, I think. And both way too young.

My cousin was a favorite of Sara and my siblings. She was full of energy. An EMT, she took care of my niece when she had a compound fracture of her arm at the remote Canada island on the Georgian Bay, calling in the Coast Guard, and keeping everyone calm. Sara was there for that. My nieces and nephews all loved her from their time spent with her in Canada. In her free time, she was all about scuba diving, and met her husband Ed through diving. They were quite a pair.

We went, as promised, to their wedding reception, which occurred sometime after the actual ceremony. Just like ours did. The only problem was her husband wasn’t there. Just a cut out of him, as he got called to work if I remember right. This wasn’t how I wanted to meet him. I wanted to meet him when the both of them finally came to visit us. Hopefully he’ll still come. And others from the gathering.

I was glad to see the mother of the first second cousin who passed away years ago. I can’t remember just when, and not sure I knew she passed away at the time. I hadn’t seen her mother in maybe 30 or 40 years, and it was good to catch up.

Last week also corresponded with alumni weekend in my hometown, and it was good to see several school mates. We’re moving up the “old” ladder at these events, with fewer and fewer of the older classes there, and we are becoming the old people. And so it goes. Listening to unprompted racist shit from people I’ve known since childhood makes me know it won’t be a bad thing when my generation and those ahead of me pass on. Hopefully the younger ones will do better. I wish I had more hope that they will. We’re all products of our upbringing to some extent.

Our childhood home is soon to be razed. The neighbor bought it, and is taking it down. And it’s time, I think. Many have lived there since my dad sold it, and most every time it was repossessed when payments couldn’t be made. The young neighbor was married to the daughter of one of our childhood neighbors across the street. He was happy to have us look around and allowed us to take anything we wanted. I took a little piece of siding that was put on when I was young. Just before we left, I reentered the house to stand in the room where my mom passed away, and that was good.

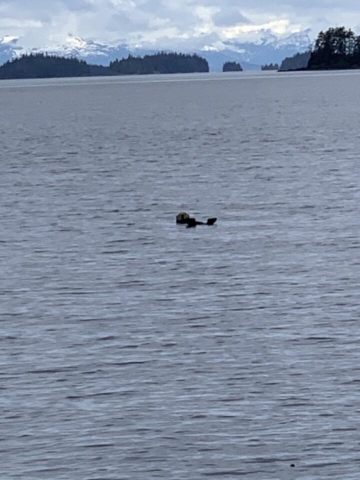

This is the 5th trip out of state since last September, between overseas volunteer fisheries assignments and funerals. Good to touch down last night on the plane home and know summer season is here and lots of family and friends coming in for boat trips over the next 2 months and I have no plans to go Outside for awhile. Glad to be back where I belong.